I think now, looking back, we did not fight the enemy, we fought ourselves - and the enemy was in us... The war is over for me now, but it will always be there - the rest of my days. As I am sure Elias will be - fighting with Barnes for what Rhah called possession of my soul ... There are times since I have felt like the child born of those two fathers... but be that as it may, those of us who did make it have an obligation to build again, to teach to others what we know and to try with what's left of our lives to find a goodness and meaning to this life.

Thematic stereotyping appears to be a necessary evil, because individuals from minorities cannot accurately live up to their theatrical stereotypes, as directed. Thus the practice of stereotyping continues. It’s unfortunate because other cultures observing American films are invited into American culture through scenes that repeatedly elicit cynical disgust from those who do not self identify with Americans. It’s a disturbing and probably irreversible cinematic trend that amounts to a propaganda campaign against the

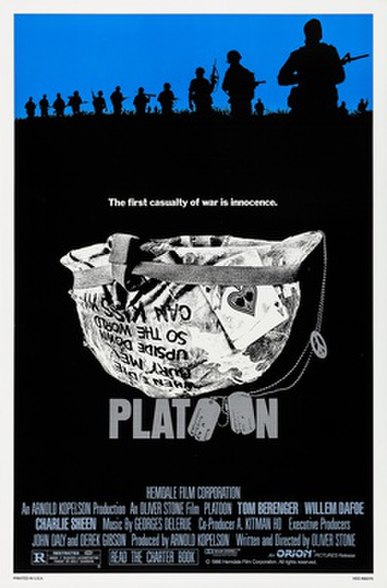

In films like Platoon, the cultural imbalance always favors the “other”. It’s a systemic and irredeemable problem with storytelling limited by the Widescreen. It’s worth mentioning because imbalanced narratives always manifest unintended consequences.

The film’s concluding quote speaks to the conflict confined to the film, not the Vietnam War. The film was about character conflict.

Elias’ character is emotionally sensitive and smart. Barnes’ character is a ball breaker, emotionally numb and stupid. The conflict between these two identities erupts fatally on the Widescreen when Elias is martyred by Barnes.

SCENE: They meet each other on the battlefield unexpectedly --- Elias assumes Barnes will keep the conflict between them political, judicial and non-violent. Elias smiles to see a fellow soldier, then, Elias’ illusion is shattered by several rounds fired from Barnes’ rifle discharged into Elias’ chest.

To the “other” in the audience, Barnes is the only character that matters. Elias is too high on mary-jane, or too philosophical, to do much about Barnes’ unrestrained rage. Indeed, Elias is shown running wildly through the enemy’s ranks, attacking shadowy but apparently legitimate enemy targets in the scene preceding his martyrdom. But there is no substance to the amorphous enemy in the film Platoon. Therefore there is no observable balance between friend and foe for an audience member who identifies more with the Vietnamese population in which the enemy maneuvers. The threat against both Elias’ and Barnes’ infantry division is muted by the film, which the film’s conclusion quote drives home even harder. “we did not fight the enemy, we fought ourselves”.

Real security gains achieved in war, as opposed to synthetic drama manufactured for a widescreen, are achieved by reaching out to and connecting with an indigenous population. The real relationship is not an insular affair but between American forces and the society they are ordered to engage. The only outsider should be the enemy of American forces and the enemies of the population American forces are sworn to protect.

Unlike a fake Widescreen War, real security is the only successful narrative. Unfortunately, it’ll never play well on the Widescreen. Real security is a reality I’m willing to advocate because it’s a historically accurate reality, proven to save lives in the field over and over again. The alternative, insular, ad homonym fights are a Widescreen drama that will cost lives in the field. Playing out the Widescreen fantasy will eventually result in the surrender of our forces and the forfeiture of friendly populations to the enemy.

Regardless of what one thinks of the film, Platoon, the last line is prescient. We have an “obligation to build again, to teach to others what we know and to try with what's left of our lives to find a goodness and meaning to this life”. If the past has anything to teach us, the lesson is; fight and defeat the enemy, not each other. That lesson is not found in a Widescreen War…